The 'Topy' of Language

I thought I might make a post of an idea that has been circulating in my head this past week. The idea centers on extending what somatopy, retinotopy, and tonotopy imply for concept representation.

Background

Somatotopy is known to exist throughout many regions of the brain. Classically, we know about the humunculus in the motor gyrus, but it is a much more general theme that neurons close together in the cortex tend to represent similar things. For a more formal definition of somatotopy, we can define it as:

Somatotopy is the point-for-point correspondence of an area of the body to a specific point on the central nervous system 1

Practically speaking, this generalizes to the retina and cochlea resulting in respective retinotopic and tonotopic maps. These maps can be explored through functional imaging as shown in the figures below:

Polar angle represented across the visual cortex

Demonstrates a down-sweep of tones

Both of these examples are taken from the website of Marty Sereno. A general question is:

Are there parameters which vary continuously vary in the language system?

If there are, how might we go about finding and exploring them?

General Approach

What is described above can also be thought of as a degree for the system. In the visual cortex, the two largest of degrees of freedom would (hopefully) be eccentricity and angle. The general problem of finding degrees of freedom for a system corresponds to dimensionality reduction. In most cases, we are interested in non-linear dimensionality reduction, for which many algorithms exist. One of the most common techniques is known as diffusion mapping, so we might try to recover eccentricity and angle in the visual cortex using this method.

Dataset

Language System

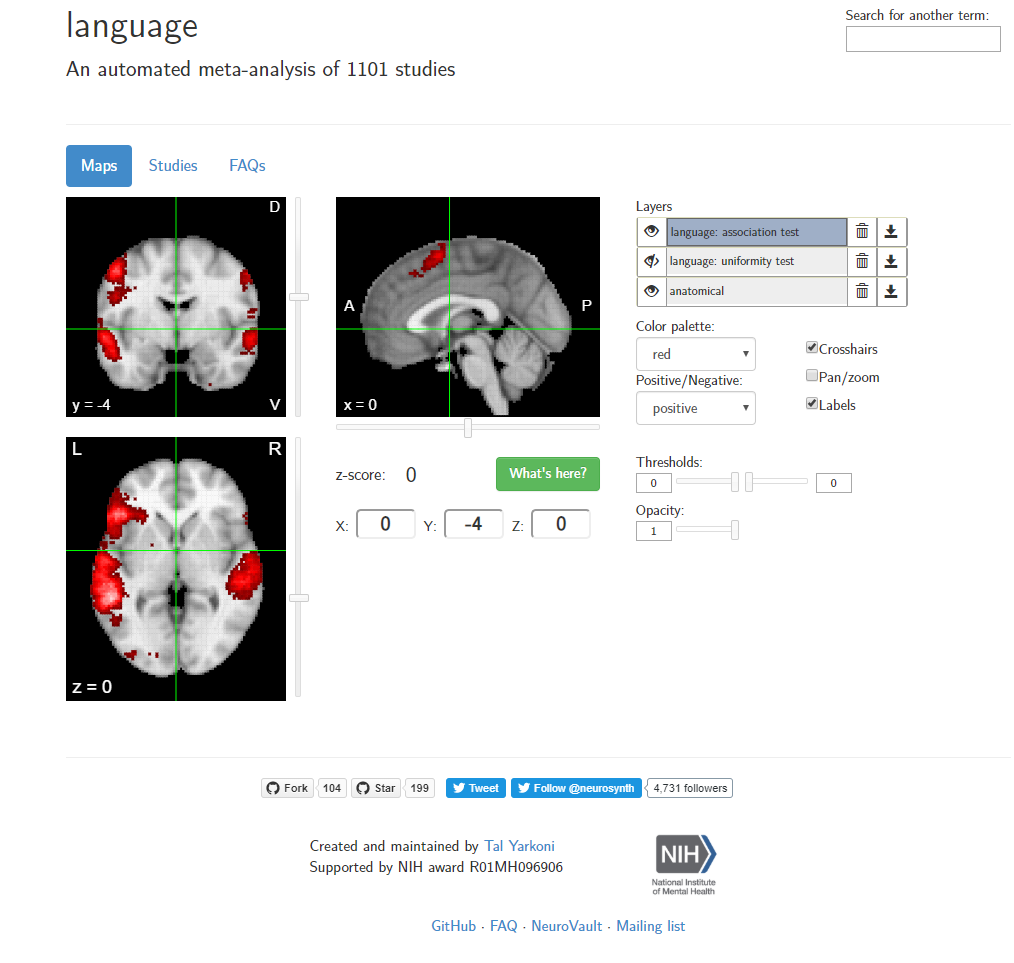

For a general idea of which parts of the brain are involved in concept representation, we can look at computer-generated meta-analysis found at NeuroSynth.

We can use this mask to select voxels of interest in MNI space. This list of masked \(\beta\)-values can then be thought of as a vector for which we can look as the question:

Are there any continuous degrees of freedom exhibited by the collection of vectors?

To do this in python, first, all the t-scores were converted into MNI space, and then the neurosynth mask was scaled and applied to the voxels.

import os

import numpy as np

import subprocess as sp

import nibabel as nib

langMask = nib.load('language_association-test_z_FDR_0.01.nii.gz') #Neurosynth-Mask

volnames = list(set([k.rsplit('.',1)[0] for k in os.listdir('alignedData')]))

wordLabels = []; patLabel = []; wordVecs = []

for vol in volnames:

g = nib.load('alignedData/'+vol+'.HEAD')

gg = nib.brikhead.AFNIHeader(nib.brikhead.parse_AFNI_header('alignedData/'+vol+'.HEAD'))

wordLabels.extend(gg.get_volume_labels()); patLabel.extend([vol.rsplit('.')[0]]*320)

resamp_mask = nil.image.resample_to_img(langMask,g)

wordVecs.append( g.get_fdata()[resamp_mask.dataobj >2,:].T ) #Threshold neurosynth mask at Z>2

allVecs = np.concatenate(wordVecs,axis=0)

The result of this is a 34,000 dimensional vector for each word in each patient which gives us a data matrix of [7,000 by 34,000]. This can then be analyzed using dimensionality reduction techniques such as PCA, tSNE, and Diffusion mapping. Unfortunately, after running these analysis, there was no ‘naturual’ ordering to the words, so for the moment, this is where my analysis ends.

References

-

Saladin, Kenneth (2012). Anatomy and Physiology. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 541, 542. ↩